The Exorcist: If You Were the Devil, Where Would You Hide?

By Steve Wagner

“He is a liar. The demon is a liar. He will lie to confuse us. But he will also mix lies with the truth to attack us. The attack is psychological, Damien, and powerful. So don't listen to him. Remember that. Do not listen.”

— Father Merrin (Max von Sydow), to Father Karras (Jason Miller) in The Exorcist

The Exorcist --Written by William Peter Blatty, Directed by William Friedkin

One crisp, cool evening (the kind we used to call “jean-jacket weather”) in the autumn of 1975, when I was fourteen, a buddy and I walked through the woods behind my house and down to the local movie theatre with hopes to somehow sneak into the “R” rated film we were too young to see legally. We wouldn’t be able to buy tickets at the box office—we would have to find another way in. After surveying our options, we decide the best bet would be to find an adult to purchase tickets for us, and then hope to get past the ticket-taker under the cover of a crowded rush of legal attendees. We found a “bum,” convinced him to buy us the tix, and with some fancy footwork in the lobby found ourselves inside, slumped low in our seats in the front row. We were ready to laugh our asses off and revel in our clandestine underage accomplishment. “Mature Audience” was not an accurate description of us that night. But we were without fear—we’d pulled a fast one on the adult world, and man were we looking forward to that vomit scene we’d heard so much about. The Exorcist was gonna be a blast!

About 90 minutes later—30 or so minutes after I had lost all feeling in my legs and on the verge of peeing in my pants—I turned to my pallid friend. He looked up through the fingers in front of his eyes and said softly, “Let’s just GO.” I shook my head no; though I wanted out of there in the worst way, his plea could be a ruse to trick ME into being the scaredy-cat, the one to get up first. Such is the logic of the teenage brain. Plus, I couldn’t really move. I was staying right where I was until the lights came on. When that finally happened, we stumbled outside, only to quickly agree there was no way we were walking back through those woods. We called my mom from a payphone, who drove down to pick us up, and who laughed at us the whole way home in a well-deserved “serves you right” manner.

The Exorcist was the most visceral, frightening, unsettling, shocking thing I had ever witnessed. I would be eighteen before I found the courage to read the book by William Peter Blatty that inspired the film, and it scared the holy hell out of me, too. This story of a young girl’s demonic possession leading to an epic battle of Good vs. Evil shook me to my small-town Lutheran-upbringing core. When I became a film critic in 1992, it naturally became the benchmark by which I judged all horror films, and as I spent the next 25 years reviewing literally hundreds of movies, I was struck again and again at its timelessness and towering influence. The Exorcist, it was clear, had defined a new cinematic genre wherein religious images are far more horrifying than CGI monsters, serial killers, or insane clowns.

Levitation Scene from The Exorcist

Here, with an unflinching camera and—somehow, amidst the vomit and levitation and head-spinning—a penetrating, character-driven plot, writer Blatty and director William Friedkin created a quintessential allegorical narrative of God and the Devil vying for the soul of an innocent unable to control or affect the forces of life—which is, let’s face it, how most of us feel most of the time, and how many of us believe the universe operates at a fundamental level. No book or film has ever done this more effectively. In fact, I suspect that if the story of The Exorcist were to be slipped into the Bible next to apocalyptic books like Daniel and Revelation, it would fit like a seemingly inspired scriptural glove.

And the story wasn’t finished with me by a long shot. Over the ensuing years, I heard rumors that the actual exorcism that inspired the book and film had taken place in my hometown of St. Louis, and further, that the Catholic priest at the church right behind my house had participated in it while a seminary student at St. Louis University in the late 1940s. This felt a little too close for comfort, but I assured myself that this was just a typical urban legend, like every college campus claiming that Animal House was based on the exploits of their most wild and depraved frat house. But then, a close friend got a job as a security guard at the “new” Alexian Brothers hospital in downtown St. Louis, and what he told me thickened the plot considerably.

The original Alexian Brother's Hospital, St. Louis MO

My friend had become pals with one of the old-timers, a janitor who had worked for decades at the original Alexian Brothers hospital, which had been demolished in the mid-70s. This man said that the infamous exorcism did take place at that old hospital, and that the room where the rites were administered was shuttered for years thereafter. He said that the older employees were all aware of what supposedly happened in that room, and further that he had been in the room several times, and that it had been left exactly as it was when the exorcism took place. He said that the ritual took weeks and had originally begun at St. Louis University. This, of course, jibed with what I had heard regarding the local priest being a seminary student at SLU. Though I had no way to verify any of this, it seemed dots were connecting, pointing to the likelihood that the inspiration for the scariest movie of all time indeed took place basically in my back yard. Which was…creepy.

This all happened to me before the age of the internet and Wikipedia, so further verification was beyond both my scope and desire; though I was intrigued, I wasn’t motivated to spend hours at the library scrolling through microfiche to seek out the truth, or falsehood, of any of these claims. But in 2012, when I had the opportunity to interview William Friedkin for the Flick Nation podcast, these modern research tools came in very handy, and I dove deep into the mystery. From what I could glean, the essentials of the story as I had heard them were quite accurate. And if anyone could further confirm those essentials, it would be the director of The Exorcist himself.

Dennis Willis (host and producer of Flick Nation) and I interviewed William for his latest offering, the darkly entertaining crime and murder mystery Killer Joe, starring Matthew McConaughey as a dusty Texas town cop who moonlights as a hitman. McConaughey’s career was resurging, and that was the commercially obvious subject matter for what would be an interview lasting only ten, maybe fifteen, minutes total. I, however, wanted to spend the entire time talking about The Exorcist, and William was beyond gracious. We discussed his notorious magnum opus for a good twenty minutes, and when the studio rep poked his head in the door to wrap us up, William waved him off and talked to us for another twenty minutes. When I told him I was from St. Louis and had heard stories about the real exorcism, he really dialed in, and not only confirmed many of the facts but also offered a few additional details, such as that the boy who had undergone the treatment in 1949 was still alive, that the Catholic church had kept tabs on him throughout his life, and that William had spoken with the boy’s aunt, who provided specifics not in the Blatty book but included in the film—such as the furniture scooting around the room. It was a fascinating conversation, and we hit it off so well that William invited Dennis and I to meet up with him a couple weeks later for a special screening of his 1981 film Sorcerer, which of course we did, relishing every moment spent with the great auteur.

Steve Wagner, William Friedkin, and Dennis Willis

Around the time of my interview with William, I began writing the book All You Need is Myth: The Beatles and the Gods of Rock (Waterside, 2019), a study of the classic rock era through the lens of archetypes, symbols, and narratives found in classical mythologies and religions. This required serious research on numerous ancient concepts, and over the course of ten years I read dozens of books written by experts in human psychology, comparative religion, and the mythologies of antiquity. While composing the chapter on the Rolling Stones, I embarked on an educational journey that I would surmise relatively few people have undertaken—a deep study of the history of the devil. It was an eye-opener, to say the least.

The first thing one discovers is the absolute paucity of material written on the subject. While there are literally thousands of books on God, Jesus, Christianity, and the religions and mythologies of the world both past and present, locating a comprehensive study of the devil archetype is difficult. There are of course countless novels using “him” as antagonist, as well as a never-ending supply of theological treatises on how to identify and avoid him, hold him at bay with religious prayer and practice, and even expel him from the human soul or faith community. But the devil himself? Not much at all. Now, I understand the devil is not a subject most people would welcome into their psyches, even as a detached study, but given the fact that billions of people believe in his existence and fear his consequence, it is perplexing that there is such a general lack of awareness, much less curiosity, about the most basic “facts” concerning him or his history as, you know, the supreme force of evil in the universe. While certainly not the most uplifting of topics, it seems like something we should know something about just in the context of basic self-preservation.

There are, by my admittedly cursory search, less than a dozen books that deal with this topic in any detached way (books of paintings and drawings, however artistically rendered, don’t count). Perhaps the only “popular” entry in the field is religious scholar Elaine Pagels’ The Origin of Satan: How Christians demonized Jews, Pagans, and Heretics (1995), an insightful and well-researched treatise that is only limited by its mostly narrow Judeo-Christian focus. Is not the devil a scourge on all the people of world, not simply those hailing from ancient Judea and Palestine or the modern adherents of those particular beliefs?

The most comprehensive study I found is A History of the Devil by Gerald Messadié, a book that delves into the personification of evil as imagined in traditions all over the world and throughout history. Here, we learn that the devil, despite his weighty significance and primeval origin stories, is a relatively recent addition to mythic and religious conception. While the “problem of evil” has long confounded human understanding, the personification of absolute evil is essentially absent in classical Egyptian, Judaic, Greco-Roman, Northern, and Eastern mythologies. Though characters such as the Egyptian Set, Greek Hades, Roman Pluto, and Norse Loki often exhibit evil aspects—trickery, lies, vanity, and a compulsion to thwart the noble efforts of the other deities (and sometimes murder them)—they don’t operate as lone actors; they occupy a seat in the celestial boardrooms of their respective mythic pantheons, and are often siblings of the munificent gods (Osiris, Zeus, Jupiter, Thor, etc.).

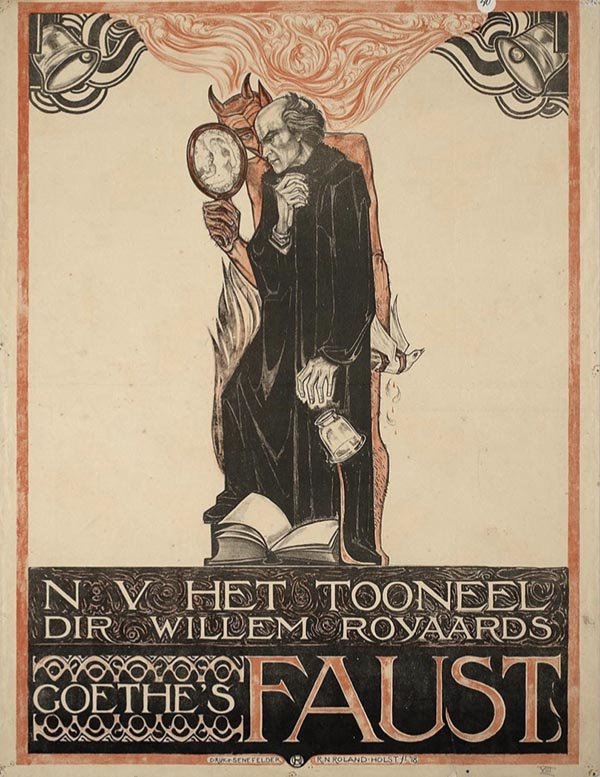

The character of the devil as we have come to understand him in the West—overseeing the damnation of souls, ruling over an eternal prison, both source and consequence of all evil—traces to the Zoroastrian religion of Persia circa 500BCE, wherein the notion of salvation became increasingly valued, assuming critical importance with the advent of Christianity. The New Testament provides several names for this character, the most prevalent being the devil (from the Greek diabolos), which means “slanderer” and “accuser,” and Satan, which translates as “adversary.” There are around thirty references to him in the New Testament, though many are found in the fever-dream prose of the Book of Revelation, and most of the rest are surprisingly brief and vague. The fact is, most of the attributes and stories we ascribe to the devil do not spring from sacred scriptures, but from literary works of fiction like Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales and Marlowe’s The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Dr. Faustus; the epic poetry of Dante (Inferno), Milton (Paradise Lost). and Goethe (Faust); and, perhaps most indelibly in modern culture, films such as Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), and The Omen (1976).

It is telling that both Pagels and Messadié, in their respective studies, posit Satan as a useful tool used by the religious to demonize political and cultural enemies. First employed by the Zoroastrians, who also invented the concepts of heaven and hell and a coming world apocalypse ending with the incineration and damnation of the “unsaved,” the people of Palestine took these ideas from their Persian conquerors to greater extremes. Beginning with the demonization of “non-believing” Jews and Roman conquerors and growing over time to include anyone deemed heretic by the priestly class, the Christians increasingly turned up the heat, leading to the centuries-long Spanish Inquisition and persecution of “witches,” i.e., “women who aren’t subservient to male authority.” Not to be left out of all the fun, Islam, essentially an offshoot of Christianity (or Judaism 3.0, if you will), has also kept this accusatory and punishing mindset at the forefront of its efforts for now over a thousand years.

When this dualistic, divisive, and desultory worldview metastasizes from the Church to the State, the cultural ground has been seeded for theocracy, totalitarianism, and fascism. And with that in mind, can anyone honestly deny who has now assumed the role of “accuser” while lording over a fearful, vengeful, and hypnotized cult? Evangelicals, who most explicitly assert the reality of the devil and who anxiously await a final confrontation where he will be defeated (and the world also destroyed in the process, damn the luck), are in the complete thrall of Donald Trump and the sinister deal with the devil he represents. If the last two thousand years of Christian history are any guide, this is not likely to end well. Because the deal he offers is not the one that has provided us so many entertaining horror stories over the years. His is the real devil’s bargain.

The familiar story, where a man sells his soul to the devil in exchange for some form of worldly power—fame, money, talent, knowledge, youth, time—is a morality tale warning of the spiritual abyss awaiting those who choose the fruits of the profane world over the sacred heavenly reward. Ubiquitous in both classical and modern art and literature and featuring tortured souls from the fictitious Faust and Daniel Webster to the real Paganini and Robert Johnson, the crossroads legend is one of modern culture’s most edifying and engaging myths.

The deal the former President offers is far more insidious and dangerous. Though never explicitly verbalized, his contract is implicitly understood by his followers, and they sign it in blood every time they vote for him or his acolytes. It is this: if they agree to keep his misdeeds, avarice, selfishness, dishonesty, and true motives from the view of the public (and the law), he will in exchange grant them the freedom from making their own moral decisions. He guarantees that they will never have to face their wrongs or acknowledge the sins of their country. If they make him their leader and provide him ethical cover, their racism, sexism, homophobia, environmental carelessness, and, most importantly, religious justification will be kept hidden and locked away. They will be freed from that most difficult of responsibilities, self-reflection, and encouraged to simply project their shadow (and wrath) onto everyone who has not also signed the pact with their dark lord. I suspect that if Dante were writing today, he would reserve a special ring in his Inferno for these duped followers whose bedazzled faith let this poisonous snake out of his gilded cage and into our nation’s highest office and, even more destructively, our living rooms.

In his 1936 essay, “Wotan,” psychologist and dream-interpreter Carl Jung analyzed Hitler’s personification of the German psyche as a furious god of “storm and frenzy.” He writes, “With Hitler you do not feel that you are with a man. You are with a medicine man, a form of spiritual vessel, a demi-deity, or even better, a myth. With Hitler you are scared. You know you would never be able to talk to that man, because there is nobody there. He is not a man, but a collective…. His Voice is nothing other than his own unconscious, into which the German people have projected their own selves; that is, the unconscious of seventy-eight million Germans. That is what makes him powerful. Without the German people he would be nothing.”

Linda Blair in The Exorcist

For nearly a century now, the people of the world have understood Hitler to be the absolute embodiment of evil, an undeniable manifestation of the devil in human form. But Jung is right in his assessment of Hitler, and the logic applies equally to Trump: there is simply no there there in either of these men. There is only rage, emptiness, absence of light. Theirs is not the voice of an individual that can be singularly considered. It is that of a collective expressing the shadow of an entire society, the mass projection of existential fear, and the desire that death befall anyone who opposes their “God-given” authority. It is a form of death cult, just as the dark distortions of our great religions are, for all their insistence that they are the only pathways to eternal life, while calling for death in the worldly realm.

And I thought The Exorcist was scary.

I would not accuse Donald Trump of being the devil, or his minions of supporting evil, because to accuse is to assume the very role I am striving to illuminate and deflate. But I will shout from the mountaintop my considered opinion, borne of thoughtful observation (and a quite easily accessible public record), that he is the supreme accuser, slanderer, and liar of our current time and culture. I also will not accuse Trump of being the devil because I no longer believe in the devil…or demons, or ghosts, or monsters. Or Astrology, or the Tarot, or “psychics” channeling the voices of deceased relatives. Or angels, or cosmic messengers, or any of the tens of thousands of gods that are the demonstrable inventions of humanity’s fearful and fertile imagination.

But what, you ask, about the boy who was possessed by the devil in St. Louis in the 1940s? Yeah, here’s the thing about that. There are many ways to interpret what may or may not have happened in that room, but the very last theory we should consider is that it was the work of the devil, a character/concept/archetype supported by no prior evidence and having even less probability of, you know, actually existing. There are numerous explanations suggested solely by the blind spots of basic human psychology, such as the susceptibility of our minds to the power of suggestion and our propensity towards confirmation bias. Consider the simple fact that the process of hypnotism is not one of inducing a “trance” state in the subject, but of imbuing them with a heightened state of suggestibility. We can even apply this method to ourselves to hopefully enhance our tendency for positive thinking and results. This is the “product” that self-help gurus and motivational coaches are selling to millions of people daily.

Ellen Burstyn in The Exorcist

Speaking of the power of suggestion, remember that Satanic panic back in the 1980s? After the publication of the best-selling book Michelle Remembers by Lawrence Pazder and Michelle Smith, which used the now-discredited practice of “recovered memory therapy” to claim Smith had been subject to ritual physical and sexual abuse, similar depravities were soon reported all over the country. By the end of the decade, over 12,000 cases of satanic ritual abuse were alleged, leading to widespread belief in a global cult involving child sex trafficking and human sacrifice. Though after countless police investigations none of those 12,000 allegations were ever proven true and recovered memory therapy has been thoroughly discredited (owing to, among other things, the heightened suggestibility produced by the hypnotism-like techniques), this mass-delusion now flourishes in the Q conspiracy madness.

Fact: even if the boy in question completely believed that he was possessed by the devil, and the exorcist completely believed the boy was possessed by the devil, and the rites administered led to the boy completely believing that the devil had thus been expelled from his body, it still would not prove in the least that the devil had possessed the boy, much less that the devil exists. Further, several investigative journalists and skeptics have researched the original case, producing studies that strongly question the supernatural claims and conclusions, and offer quite rational explanations for the boy’s behavior. Mark Opsasnick, after interviewing many of the boy’s neighbors and childhood friends for his in-depth article “The Cold Hard Facts Behind the Story that Inspired ‘The Exorcist’” (Strange Magazine, 1999), established that much of the story was based on hearsay, was not documented or fact-checked, and further that the boy had been “a very clever trickster, who had pulled pranks to frighten his mother and to fool children in the neighborhood.”

Noted skeptic and paranormal investigator Joe Nickel, who has debunked numerous claims of miracles and proven many religious artifacts, including the Shroud of Turin, to be forgeries, in his article “Exorcism! Driving Out the Nonsense” (Skeptical Inquirer, 1993), determined that what “began as a seeming poltergeist outbreak, soon advanced to one of alleged spirit communication, before finally escalating to one of supposed diabolic possession.” He concluded that “nothing that was reliably reported in the case was beyond the abilities of a teenager to produce. The tantrums, ‘trances,’ moved furniture, hurled objects, automatic writing, superficial scratches, and other phenomena were just the kinds of things someone of [his] age could accomplish, just as others have done before and since. Indeed, the elements of ‘poltergeist phenomena,’ ‘spirit communication,’ and ‘demonic possession’—taken both separately and, especially, together, as one progressed to the other—suggest nothing so much as role-playing involving trickery.’

The good news is the devil doesn’t exist. The bad news is Donald Trump does. The threat he embodies is a real one, and we must get real to survive his menace. We need to separate church and state, not just in our government and laws, but in our minds, in our beliefs, in how we meet the challenges of life. Fearing the non-existent character of the devil and the non-existent threat of being cast into a non-existent hell is not only a waste of our precious, miraculous (yes!) consciousness, it allows a true existential threat like Trump to operate in the shadows of our perception, to manipulate us through our fear of things we don’t yet understand about the mysteries of existence, the mysteries of ourselves. Regarding Trump, I suggest we take heed of Father Merrin’s advice to Father Karras in The Exorcist: “He is a liar. The demon is a liar. He will lie to confuse us. But he will also mix lies with the truth to attack us. The attack is psychological, Damien, and powerful. So don't listen to him. Remember that. Do not listen.”

The demon Pazzuzu in The Exorcist

Exactly. Don’t listen to him. He is a liar. But keep a very close eye on him, and flood him with a spotlight so bright that he is fully exposed, examined, and understood for what he really is—an expression of our darkness railing against the light.

It is ironic that the concept of “illumination” is woven into the very fabric of our creation of the devil, as seen in one of our chosen names for the character himself. Consider: one of the key tropes in Judeo-Christian mythology is the casting out of Satan (and angels loyal to him) by God following a primordial “war in heaven.” This celestial drama, alluded to in Luke and expanded upon in Revelation, seems to have its genesis in a passage from the Old Testament Book of Isaiah, “How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning! How art thou cut down to the ground.” But it is likely an ancient astrological concept predates Isaiah. In the Hebrew and Latin languages, the planet Venus is called “Lucifer.” Venus (the Morning Star) was seen as a challenger to the light of the Sun (the Day Star); thus, the word Lucifer also provides the adjective, “luciferian,” meaning “light-bringing.” In English we have the derivatives “lucid,” “lucent,” and “translucent.”

The idea of ongoing war between light and dark is perhaps best understood through Jung’s psychological concept of the shadow archetype, which describes the hidden, dissociated aspects of the human unconscious. When not integrated into the conscious personality, the shadow is often projected outward and can become the basis for what is now understood as multiple personality disorder. Indeed, Pagels delineates Satan as a “reflection of ourselves and how we perceive ‘others.’”

Max Von Sydow in The Exorcist

While Hollywood will likely continue to rely on dramatic battles to illuminate our struggle to triumph over the power of shadow energy, Jung believed that evil wasn’t something to defeat, but rather to understand and incorporate: “The more negative the conscious attitude is, and the more it resists, devalues, and is afraid, the more repulsive, aggressive, and frightening is the face which the dissociated content assumes… Recognition of the reality of evil necessarily relativizes the good and the evil likewise, converting both into halves of a paradoxical whole.” In other words, all we need to do is turn the light on. Then we will see that the room is empty, save for the mirrors reflecting our fears back at us.

It should be obvious at this point that the devil hides in “The Church”—hell, they invented him in the first place. And you can bet they are going to keep him there, for their power, like that of unprincipled politicians, derives solely from our mistaken belief that they, and only they, can keep us free of his clutches. And they must keep him in the dark, because if he were to be exposed to the light he would quickly diminish, and eventually, God forbid, disappear.

Steve Wagner was co-host, writer, and executive producer of the Bay Area television programs Reel Life and Filmtrip, reviewing over one thousand films and interviewing over three hundred actors, directors, writers, and musicians. As a director of the San Francisco Art Exchange gallery, he brokered sales of many of the world’s most famous original album cover artworks, including Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon. He has ghostwritten or collaborated on several published books, contributed articles on music, film, and popular culture to numerous publications, and is the author of the book All You Need is Myth: The Beatles and Gods of Rock (Waterside, 2019), a study of the 1960s music renaissance through the lens of classical mythology.