Cinema Paradiso: Life Reflections and Love Stories

By Steve Wagner

“You have to go away for a long time, many years, before you can come back and find your people.”

— Alfredo, to Toto in Cinema Paradiso

In 1995, I was co-producing, writing, and hosting a weekly television show about movies called Reel Life for a small Bay Area cable access station with my colleague Dennis Willis. We were still holding down regular jobs and creating the show by the seat of our pants, squeezing in movie screenings, taping interviews, and dealing with the arduous task of producing around the confines of our two demanding schedules. Building an hour-long program every week at a level that even approached broadcast quality (before digital technology was available—a time that now seems prehistoric) was wearing us out. One of the solutions we came up with was to produce as many “ever-green” shows as possible, programs that weren’t dependent on the timeliness of current entertainment news and theatrical releases, but on subjects that wouldn’t be dated if the show was repeated.

One of the best of these “generic” shows, as we called them then, was a look at what we thought were the most influential films of the previous decade, the years 1985 to 1995. Several were obvious; offerings such as Die Hard, When Harry Met Sally, and Pulp Fiction had clearly become plot and structural templates already copied many times in just a few short years. Others were chosen for their effect on the business of cinema, which by 1995 had become as firmly ensconced in the local video store as the movie theatre. For instance, 9 1/2 Weeks, which found a then-surprisingly strong following upon its VHS release, effectively opening the door for a “Hard R” or “soft porn” genre that would thrive on home video (many people and couples embarrassed to attend these films in theatres rented the holy hell out of them on tape). Also, Sex, Lies, and Videotape, which established the true advent of the “independent” film genre and the financial potential of inexpensively produced films outside the Hollywood system; Roger and Me, Michael Moore’s socially conscious breakthrough documentary that took this once considered highbrow genre into the commercial mainstream; Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, which marked a huge leap forward in the difficult marriage of animation and live-action, defining a quality standard that has arguably never been bettered, even in the “anything is now possible” digital age; and, our focus here, Cinema Paradiso, the ecstatic commercial reception of which provided the typical American viewer the tacit “permission” to enjoy and consume international films, revived a faltering Italian film business, and effected a global film industry sea-change.

Written and directed by Giuseppe Tornatore in 1988, Cinema Paradiso had an interesting journey to its eventual classic status. Originally released in Italy in 1988 with a 155-minute running time, the film received a tepid response. Its distributer, Miramax, then insisted that it be edited down to a tight 123 minutes, and this version was an immediate hit with both audiences and critics, leading to an awards bonanza the following year when it won the Oscar and Golden Globe for Best Foreign-Language Film, the Grand Prix Jury Prize at Cannes, and swept the BAFTAs in numerous categories. Though Hollywood directors had long cited the influence of international auteurs, commercial success for “foreign” films had been quite elusive in the United States prior to the phenomenon of Cinema Paradiso. In the years since, we have witnessed one international hit and awards juggernaut after the next: Il Postino: The Postman (1995); Life is Beautiful (1998); Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000); The Sea Inside (2005); The Artist (2011); Amour (2012); Roma (2018); and Parasite (2019)—the last of which won Academy Awards for both Best International Feature Film and Best Picture.

The influence of Cinema Paradiso is clear, and its inclusion on countless “Best Films” lists is a testament to its beloved status the world over. So, I will come clean early: Cinema Paradiso is my most cherished film, and not because of its influence on me personally, or my career, or my art, but because of its sympathy with my heart, uncanny reflection of my personal experiences, and timelessness as a beautiful and touching reminder of what is really important in my life. In fact, the film is so reflective of my experiences that writing about it produces a feeling of vulnerability, a sense of emotional nakedness that I rarely experience when writing about anything. Hence the opening paragraphs of this very article. Admittedly, I needed to ease myself into this somehow, to find a way of simply beginning to write about this film, because the context, for me, could not be more intimate.

Let’s first consider the basic plot of Cinema Paradiso: In Rome, a successful film director, Salvatore Di Vito, learns that a man named Alfredo has died. Clearly shocked by this news, Salvatore flashes back to his youth in mid-forties post-war Sicily.

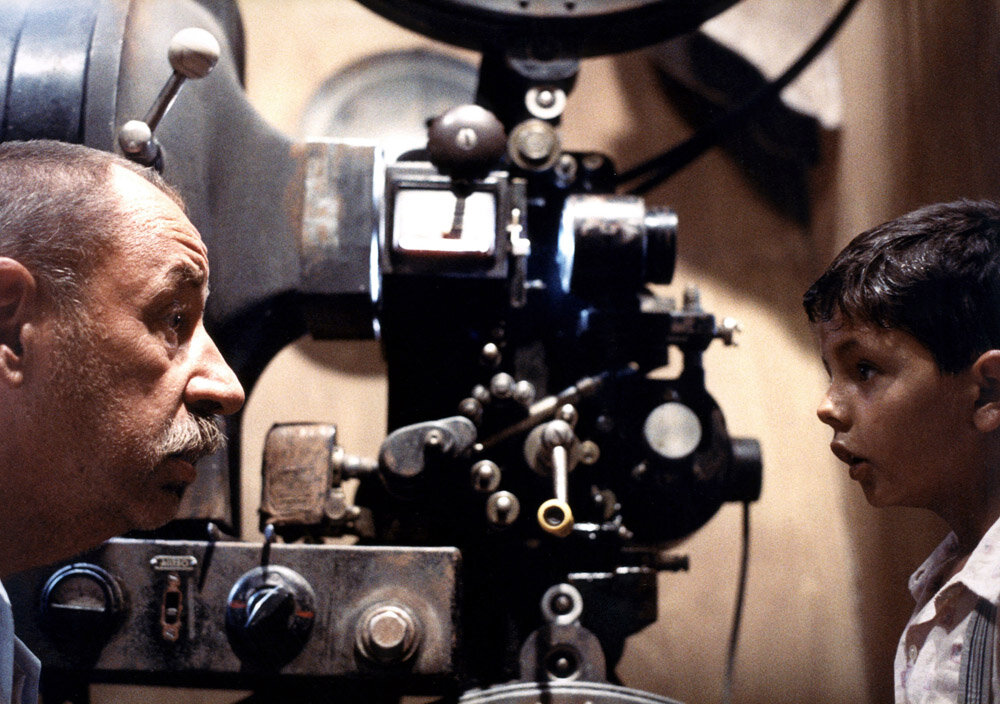

A mischievous child, Salvatore, nicknamed Toto, spends his days sneaking into a local movie house—the Cinema Paradiso—trying to worm his way into the good graces of the projectionist, Alfredo, who eventually warms to the boy and teaches him to operate the projector. This greatly consternates Toto’s mother, a war widow doing her best to raise the boy by herself. With time, she comes to understand that Alfredo has become a crucial father figure for her son, a responsibility that Alfredo has touchingly already assumed out of love and empathy for the boy. One night, a fire breaks out in the projection room, and an explosion of nitrate film leaves Alfredo blind. With Alfredo now unable to continue as projectionist, young Toto is hired, as he is the only other person in town who can do the job.

In his teens, Toto continues to work at the Cinema Paradiso, and after acquiring a home movie camera begins experimenting with his own films. One day while filming at the train station, he glimpses a girl, Elena, and becomes smitten with her. Toto sets about to win her heart, and though his expressions of love are initially rebuffed, eventually Elena comes to share his feelings. But the romance is short-lived; Toto must report to conscripted military service, while Elena is forced to move away with her family. Heartbroken, Toto seeks Alfredo’s advice, and the old man implores him to leave their small town of Giancaldo and pursue his dreams of making films. Shortly thereafter, Toto bids goodbye to his family and Alfredo.

Now middle-aged, Toto returns to Giancaldo to attend Alfredo’s funeral, where he reunites with his family for the first time in 30 years. He visits Alfredo’s widow, who gives Toto a small reel of film that Alfredo has left for him. Upon returning to Rome, Toto watches the reel and discovers it to be a montage of the passionate kissing scenes that Alfredo, on the order of the local priest, had spliced out of the many films he projected at the Cinema Paradiso. Tears well in Toto’s eyes and he smiles, finally, we surmise, at peace with his past. Fini.

Jump cut to my personal story. In 2016, after living for nearly 25 years in San Francisco, I accepted the position of director for an art gallery in Carmel-by-the-sea on the central California coast. I rented a small, furnished cabin in nearby Big Sur, and commenced a grueling, 60-plus hour work week while hiking the stunning coastline in my rare off-hours. But my new life chapter was to be cut short—the Big Sur fire in the summer of 2016 (at the time the biggest fire in California history) forced my evacuation for several weeks and left nearby Carmel a smokey ghost town. Then came the fall rains, which, while finally extinguishing the fires, caused devastating mudslides forcing the closure of many miles of Highway One, essentially the only access to and from Carmel and therefore, my gallery.

With the local art business in peril and my position now uncertain, I weighed my options and contemplated my next move. I had for years wanted to visit my hometown of Manchester, Missouri to spend quality time with my widowed mother, who had by that time been living alone for ten years. So, I left the gallery, packed my bags, and drove dozens of hours through rain and snow to the town of my youth, the home where I grew up, the room where I slept for the first 18 years of my life, and my elderly mother’s open arms.

Within a short time, the inevitability of relocating to Missouri permanently became clear in my mind. Though my mother was in excellent health in her late eighties, at her advanced age she would need increasing assistance if she were to stay in the family home. I knew that I should be the one to be with her for many reasons, not the least of which was her unwavering support throughout my entire life, even when my career and aspirations took me far away from her for decades. After a short time, I gave up my apartment in San Francisco (which I had been renting since my move to Carmel) and remained in Manchester to live with Mom.

The surface parallels between my life story and the Cinema Paradiso narrative are hard to miss: The devastating fire that changes the arc of a life; the return to the small hometown following the loss of a father; an aging mother living alone and patiently awaiting the presence of her son. These analogies hadn’t yet existed for me as I viewed the film many times over the years, but now feel so prescient that I’m awed at how great art can affect one on so many levels. What once were tears shed for the fictional character of Toto are now deep emotions impossible to separate from my own memories. Now, back at home with my mother, with perspective that can only come with age, I find viewing Cinema Paradiso to be an archetypal journey through my own intimate hall of existential mirrors.

Anyone who visits their hometown after many years knows the powerful feelings of déjà vu that can emerge unexpectedly. A breeze felt on the patio, scent wafting from the kitchen, sunset glimpsed over a familiar hillside, hello from a neighbor on the street, or sight of kids playing ball in the park can catapult me back to my childhood. For me now, these echoes often carry the sound of my father’s voice. Indeed, his energy can be felt in every inch of our family home and property. He planted every tree in the yard. He built the deck where I write in the summer and remodeled the basement where I write in the winter. He poured the concrete in the driveway, laid the railroad ties that surround the flower beds, built the garage where we park the car. He built the master bedroom in the back of the house where my mother sleeps, and the den in the front where we watch television and nap on the couch. It was in this den that I said my final goodbye as he lay dying from pancreatic cancer. Every day, I am aware he is still taking care of our family.

Alfredo reminds me very much of my father. They were of the old school. They taught us the important things so that we would grow from boys into men. They worked tirelessly so that others might enjoy life, and they never sought nor expected any recognition for their good deeds. They had calloused hands but soft eyes. Their gruff demeanors couldn’t mask their enormous hearts. Like Toto, I have returned to a place no longer graced by my father’s presence but absolutely permeated with his spirit.

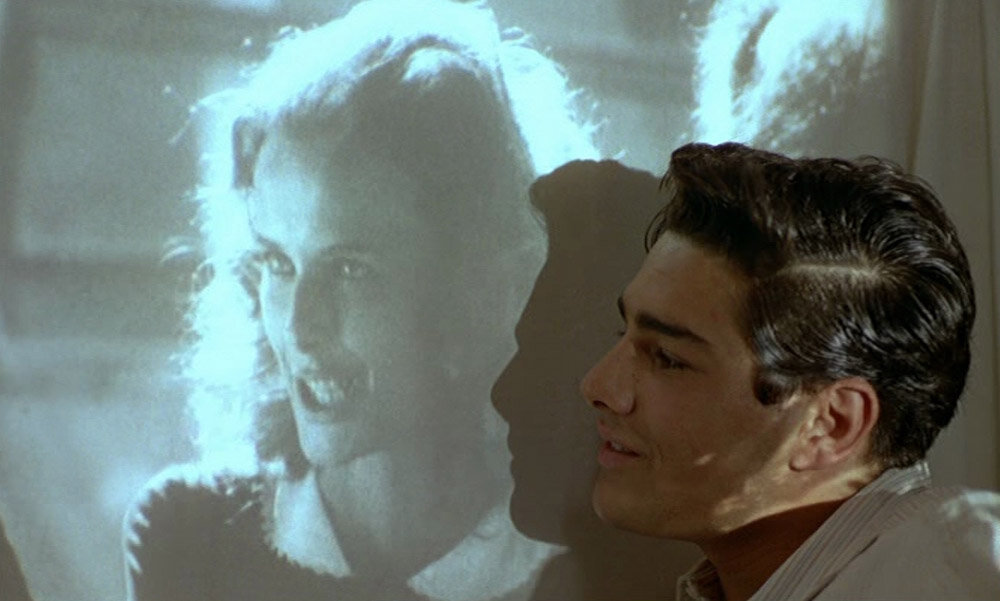

In the Cinema Paradiso narrative, Toto’s first love, Elena, is (after Alfredo) the most vital character in the plot; the middle act of the film is almost solely dedicated to their relationship. As Toto surveys his teen years from an adult perspective, he recalls the day when, while shooting random footage with his home movie camera, he sees her for the first time and instinctively films her as she walks with her family. A scene toward the end of the film, where Toto views this footage while alone in his bedroom, his mother careful to not interrupt his personal moment, is among the most poignant in the movie. This short snippet of footage represents Toto’s idealized vision of Elena, a symbol of love discovered, and love lost, that we understand has haunted him throughout his life.

Once again, I identify with Toto, for I too have an “Elena” in my long-ago past, a character who makes far more appearances in my dreams than in my conscious thoughts or memories. Viewing Cinema Paradiso now, surrounded by the memory triggers of my youth, I am overwhelmed by how viscerally decades past can feel like yesterday when matters of the heart are evoked.

I remember well the day I met her. It was spring 1978, my junior year of high school. Outside a typical suburban house party, I sat in my car with a buddy, smoking a joint and knocking back beers, as was the custom of the time. We spotted her and another girl doing cartwheels and gymnastics routines in the front yard, and my friend shrieked, “Oh, my god, they’re drunk!” He rolled down the window and invited them to join us in the car, and surprisingly, they did.

A bit of backstory: I had known of her for several years, but had never given her much thought, if any, and had never spoken to her before. Though the schools we attended were small enough that everyone more-or-less knew of everyone else, the social cliques of that time kept us somewhat socially sequestered within our specific groups (which I assume is likely still the case at most schools). In the popular lingo of the time, I would have been considered a “freak,” while she was a “soc,” or its more intimidating sub-group, “brain.” In other words, while she was studying rocket science, I was studying rock & roll. While she was cramming for the next exam, I was smoking in the boy’s room. To use a Broadway analogy, I was Harold Hill and she was Marion the Librarian.

So, there we were, two freaks in the front seat and two brains in the back. I was behind the wheel, and my Elena was cattycorner in the back seat, and all four of us were, as they said in those days, “wasted.” My buddy was doing most of the talking, teasing them for being tipsy, when I glanced into the rear-view mirror to find my Elena looking at me inquisitively. I turned to look at her, and the lightning bolt struck. It sounds so cliché, but it was true—the moonlight was illuminating her face, gleaming with a slight perspiration from the activity in the front yard, and I saw how beautiful, indeed perfect, to my mind, were her features. Who was this person I had ignored for years, who seemingly became a woman overnight? She stared at me curiously, then blurted, “You’re Holden Caulfield.”

I’d guess now that this was an impulsive slip of liquor’s loose tongue, but for me then it was a sign that she saw something in me, something I already suspected about myself: I thought I was quite a bit like Holden Caulfield. The universality of Salinger’s protagonist wasn’t lost on me; I’m sure nearly everyone who reads Catcher in the Rye at that age sees themselves, to some degree, in Holden. But I shared so much with his character—idealism to a fault, emotional transparency, nervous verbosity, and a need to put pen to paper as a way of personal expression, exploration, and exorcism. I remember thinking, perhaps naively, perhaps accurately, “if there is one person at my high school that is most like Holden Caulfield, it’s probably me.” Even then I knew this was not necessarily a good thing, but that’s how I felt. How could this girl see that after only being in my presence for a matter of minutes?

Like Toto, I spent months in pursuit of my Elena, who halted my advances many times before coming to my arms. Also, like Toto, after she left town, I spent most of my time waiting impatiently for the mail to arrive with words from her that could somehow make my dream feel real again.

I need say no more. No amount of detail could impart it, just as the story of your Elena or Toto could never make me truly feel what you felt when you first allowed your tenderness, braved your vulnerability, and witnessed the bright light inside another person and realized it was made of the same stuff that shines inside you.

There is, I think, an important insight to glean from Cinema Paradiso, and it is oddly to be found in the contrast between the different versions of the film. As touched upon earlier, Tornatore’s original edit was 155 minutes, which he then trimmed to a theater-friendly two hours for the international release. In 2002, Tornatore released his director’s cut, which clocked in at an epic 174 minutes. This version greatly expands the Toto and Elena love story, with a denouement that functions as mini sequel to the international version. Here, Toto tracks down Elena following Alfredo’s funeral. The two find themselves together once more at a familiar romantic haunt of their youth, where they express much before making love in the car. They then realize with age-weary wisdom (and she before he, as always) that they must return to their separate lives once again, after all.

The shorter film, the version without this extended narrative, is for me the better and more meaningful picture. Although the depth to which I already loved Cinema Paradiso made me desire to know what might have happened later in life between these characters, the fact is I don’t require that resolution, and neither should Toto. Because, resolve what exactly? Toto is here still looking outward for a sense of his own worth, trying to locate meaning in the reflection of others, unable to heal his wounds through personal acceptance and forgiveness, and, finally, love of self. This has in fact already been alluded to at the start of the film: When Toto’s mother calls with the news that Alfredo has passed, the phone is answered by a woman we discover to be another in a long line of Toto’s lovers. His mother even makes a point later of telling Toto that there is a different woman’s voice on the end of every call she makes to him, and further that she never senses love in those voices. Toto, and we, would do well to believe her.

The expanded narrative in the director’s cut also changes the arc of the story and our perception of the film’s essential message significantly, and not in a good way. First, it skews Alfredo’s character as, while still wise, controlling of Toto’s future in a way that is disconnected from his principal advice to the young boy—that Toto should find his own path in life. Alfredo’s deception introduced in this longer version may make possible some additional drama between Toto and Elena but undercuts the totality of Toto’s enlightenment at the end of the film. Not only does this additional chapter represent the movie’s only real plot contrivance, even within its magical realism trappings, it obscures the only true resolution needed: Toto’s relationship with his mother.

She’s there, mostly in the background, the entire film. During Toto’s younger years, we witness her sadness and strife, unwillingness to accept that her husband will never return from the war, concern for her children on the edge of starvation, and difficulty handling her strong-willed son—who spends the family milk money on movie tickets. We watch her reluctantly acquiesce to his relationship with Alfredo, who she comes to understand has her son’s best interests at heart. When Toto meets Elena, his mother disappears from our view, only to appear briefly at the train station as Toto prepares to leave Giancaldo. Though we see them embrace, the dialog in this scene is reserved for Alfredo, and the last person we see waving as the train leaves the station is, ironically, the town priest, who has watched the power of his office recede as the town-folk increasingly value the movies over the church. But, in the end, it is only Toto’s mother that can give him the acceptance that an endless stream of lovers, and even his first love, Elena, could not provide. The director’s cut attempts to reframe this absolution through Toto’s reconnection with Elena, and the somewhat hackneyed twist that “he never saw the note she left for him at the Cinema Paradiso!” Yet, even with this revelation, and the passion that ensues, Toto and Elena remain star-crossed. It was not enough.

The fact is, in every version of the film, it is the short, quiet scene toward the end of the film between Toto and his mother that provides the emotional center, real catharsis, and most valued reconciliation. Here the gorgeous, nearly always-present Ennio Morricone score halts abruptly, and we see Toto slumped at the dining room table in his mother’s home. Intuiting his confusion, she asks what he is thinking. He replies that he thought the memories that haunted him had been put to rest by time, but he now feels right back where he started, as though no time has passed at all. He then apologizes, admitting, perhaps for the first time to himself as well as to her, “I deserted you.” Her response puts his guilt, and in a way his past, to rest. She explains that she always understood why he made his choices, that she knew his life was not meant to be lived in Giancaldo, that he pursued the life he needed and should have no regrets. “Let it go,” she counsels. This understanding and wisdom also lilts in my mother’s voice when we discuss regret. Like Toto, I needed to hear these words from the one person who loves me without hesitation, who sees me the most clearly, and who forgives my mistakes, my frustrations, my absence.

I’d seen Cinema Paradiso perhaps two dozen times in my life, and always been puzzled by the film’s opening shot: in the foreground we see a flowerpot, in the shape of a bowl, sitting on a deck wall with a vast, blue ocean in the background. This shot remains static for nearly a minute as opening credits fade in and out, before the camera begins pulling back slowly, eventually bringing us inside Toto’s mother’s home, where she sits at the dining room table trying to reach her son by phone to give him the news about Alfredo. It is here that Toto and his mother later have their conversation, essentially the final bit of dialog in the movie.

Watching Cinema Paradiso now, in my mother’s home, I feel I’ve come to understand what Tornatore meant to convey with this opening image. The flowerpot represents a vessel, a chalice, a grail if you will—a mythic symbol (as is the water in the ocean that frames it) of the divine feminine. Deepened by the pull back inside a home and the reveal of a mother reaching out to her son, we might intuit that she will here again provide a safe container and nourish him once more. The vital message of the film, perhaps hinted at in its first image, is the healing power of love within the safe harbor of acceptance.

Of course, Cinema Paradiso’s ultimate artistic triumph is that the love expressed through its characters is reflected throughout in the film’s unabashed love for the art of cinema itself. Never has a movie about movies loved movies more than this one, and this meta-statement is as personally relevant to me as its curiously reflective plot is to the story of my life. I have worked as a film critic in various capacities for nearly thirty years; dissecting archetypal plot, character, and symbolism in film has been my stock in trade for most of my adult life. Exploring and seeking to explain the mysteries of life through this medium is for me intrinsic to my individuation process, not just as a writer trying to express truth, but as self-psychoanalysis and a way to increase mindfulness of both myself and the world. My Achilles heels as a writer about film have usually tended toward one of two opposing extremes: a cynicism borne from an excess of life experience, and a sentimentality that clouds my greater awareness. Both blur my objectivity; neither the misanthrope nor the idealist in me are enough, on their own, to bring the detachment that is the purview of the truly incisive reviewer. With Cinema Paradiso, these issues—for both the characters and for me as viewer—are reconciled through love at all levels.

Indelibly expressed by the movie’s final scene, the now iconic montage of censored cinematic kisses spliced together by Alfredo as his final gift of love to Toto, is for me the most moving in all of film. Here, my cynical shadow is illuminated, and my sentiment finds a deeper purpose. All that remains is gratitude and love for everyone and everything. Damn the details, the regrets, the desires, the judgements, the guilt. This loving homage exalts human passion yet still reminds that while physical love may bloom and wilt, in temporal time, the meaning of love is, or should be, or can be timeless. Tornatore needed say no more. As for Toto, so for me. And, if I may wish, so for you.